BREAKING THE MOLD:

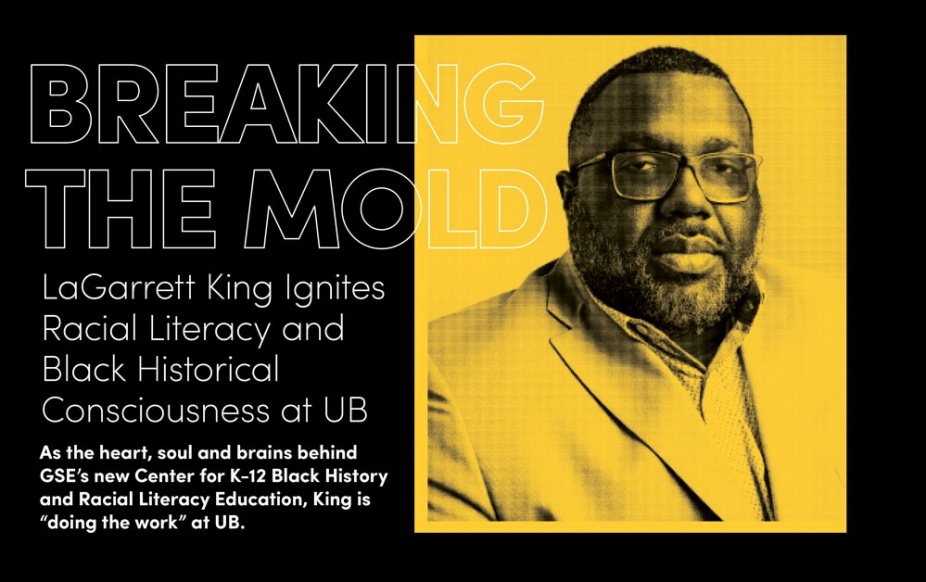

LaGarrett King ignites racial literacy and Black historical consciousness at UB

BY DANIELLE LEGARE

It’s 11 a.m. on a Saturday in February. Almost 200 graduate students, teachers, faculty members and history lovers from around the globe gather on Zoom to spend an hour together learning about Black history and racial literacy. As the learners wait for the presentation to begin, Beyonce’s “Love On Top” plays in the background. Smiling faces fill the virtual audience, some of whom have pens and notebooks in hand, others swaying to the beat of the music.

Black History Nerds Saturday School, a professional development series for anyone interested in learning about Black history and race, is now in session. LaGarrett King is the self-proclaimed “HNIC,” or Head Nerd in Charge.

King is an associate professor of social studies education and the director of the new Center for K-12 Black History and Racial Literacy Education at the University at Buffalo. He is also the mastermind behind these sessions.

Once Saturday School starts, King creates a warm, engaging space and encourages introductions and conversation. Comments fill the chat: “Good morning!” “Greetings from Philadelphia!” “Hello from Buffalo!”

A community is quickly established. Everyone has a seat at the table to share perspectives and ask questions about Black history when King hosts an event.

“I’m a nerd. If you get up in the morning, grab your coffee and get on the computer to learn about Black history on a Saturday—and you’re a teacher—you’re definitely a nerd as well. I like to learn from other people, so I invite folks to do workshops about certain Black history or racial education topics for teachers and others who want to learn more—whether it’s more content knowledge or a pedagogical approach,” he explained.

This week’s presentation, “Historical Literacy as Racial Literacy,” is with Dr. Yolanda Sealey-Ruiz of Columbia University’s Teachers College. She salutes the audience: “Good morning, nerds. Nerds unite!”

Throughout the hour-long presentation, attendees learn about the meaning of racial literacy from Sealey-Ruiz. She explains that racial literacy is a tool, a tour guide, a way to heal. And racial literacy is a way to teach, which is perhaps most relevant to today’s audience of educators.

“Racial literacy in teacher education calls for self-reflection and moral, political and cultural decisions about how teachers can be catalysts for societal change—first by learning about systems of injustice and then explicitly teaching their students about what they have learned through the use of dialogue, critical texts, journaling, and helping to develop their critical thinking and conversation skills around the topics of racism, discrimination and prejudice,” she said.

She asks for self-reflection from the audience: “What were you taught about race and racism as it relates to world history? Where and from whom did you learn what you know?” Many nerds chime in. Some announce they learned from their grandparents, others from American writer and activist James Baldwin. A few express that they learned about racism’s relationship to history during humanities classes in high school, while others share that they waited until college for lessons taught by Black professors. One nerd reveals that learning about race didn’t occur until adulthood.

“What were you taught about race and racism as it relates to world history? Where and from whom did you learn what you know?”

As the session concludes, audience members clap, snap their fingers and jump out of their chairs with gratitude. With a smile plastered across his face, King is equally appreciative of Sealey-Ruiz’s presentation. In just one hour, she offered rich, detailed lessons about history and teaching, and gave attendees suggestions for further learning and self-reflection.

What is the cost of gaining a deeper understanding and new perspectives through the Black History Nerds Saturday School? Nothing. It’s free for anyone who wants to enrich their Black history education.

Black History Nerds Saturday School is one of many events hosted by the new Center for K-12 Black History and Racial Literacy Education. A hub for research and professional development, the center has one fundamental mission: defining Black history education.

“Doing the work,” as he says, is always top of mind.

How are Black history and race taught and learned around the world in K-12 schools, teacher education programs and other educative spaces? King hopes to move the needle in answering these questions.

The development of the center and its lineup of events are timely. In 2022, critical race theory is under attack, books addressing race have been banned in school libraries, and teachers in many states are no longer permitted to talk about race in the classroom. Administrators, policymakers and educators need resources and clarity to best serve students and make informed decisions about teaching history and race.

King joined GSE in January 2022. Before his move to UB, he founded a similar center—the Carter Center for K-12 Black History Education—at the University of Missouri. His efforts there were celebrated: He was awarded the Isabella Wade Lyda and Paul C. Lyda Professorship, supporting his Black history education research.

Now at UB, King is the heart, soul and brains behind GSE’s new center. He is hyper-focused, generating a six-month schedule of events and programming after only a few weeks at UB. When speaking about his work, he’s serious yet smiling, focused yet funny. It’s clear his mind never stops. Research, teaching and making an impact in the community are passions and priorities.

“Doing the work,” as he says, is always top of mind.

Dawnavyn James, kindergarten teacher and doctoral student in the Department of Learning and Instruction, knew she wanted to work with King after attending and presenting at his past events. James, who will serve as a graduate assistant in the center beginning in the fall 2022 term, often wonders about the many thoughts and ideas perpetually floating through his mind. “He always has a goal in mind. He’s always thinking of something new—and it’s going to be successful, whatever it is,” she said.

As he moves forward in his new role at GSE, he is focused on getting the center off the ground to provide Black history education and support to those who need it the most. “I envision the Center for K-12 Black History and Racial Literacy Education as a very prominent space where K-12 educators, policymakers, teachers and other university personnel come to help us understand the effectiveness of how we should approach notions of Black history education, as well as try to understand the nuances of race and racial literacy,” he said.

From left to right: GSE Dean Suzanne Rosenblith, Dr. Dann J. Broyld of the University of Massachusetts Lowell, Dr. LaGarrett King, and Dr. Langston Clark of the University of Texas at San Antonio pose at the Welcome to Western New York event in March 2022.

Suzanne Rosenblith, GSE dean and professor, recognizes the significance of his efforts. “By focusing his work on Black history and Black history curriculum, LaGarrett is telling an important story. He is telling the story of people who have been completely omitted from the historical record even though they have had these amazing contributions to education in the United States. And I think this work is critically important,” she said.

While Rosenblith believes that King’s work has the potential to impact teachers around the world, she thinks that the center and its programs are especially needed in the greater Buffalo area. With Buffalo’s racial and ethnic diversity, she hopes that local teachers will find new inspiration, tools and techniques from attending the center’s events.

King is confident that the center will help teachers and administrators find ways to amplify the ignored voices of Black people throughout history through K-12 curricula. “The problem is that our U.S. history curriculum dehumanizes those who are people of color. If we understand notions of Black history, then maybe our society will understand Black people,” he said.

Originally from Baker, Louisiana, King was interested in social studies and history from the time he was young. “As a child, I always thought that what we were learning didn’t make sense or was incomplete. For me, it just didn’t make sense that white plantation owners and their enslaved people were just happy-go-lucky,” he explained. “It just didn’t make sense that people didn’t fight back from all the aspects of oppression. As a young kid, you don’t have the language to express it, but you know something’s wrong.”

He was hungry for clarity—a complete picture of history. He dug into his parents’ encyclopedias to read about different periods and pieces of Black history. Over time, it started to click. “I don’t know exactly when I fell in love with Black history. I just knew it wasn’t in our schools,” said King.

“I wanted to answer the question: What is Black history? Because we have not answered that question as a country.”

King went on to earn his bachelor’s degree in secondary social studies education from Louisiana State University. After graduating, he became a classroom teacher in Texas and then Georgia, with a period spent teaching at Booker T. Washington High School, the alma mater of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. After an eight-year teaching career, he returned to Texas to enroll in the curriculum and instruction PhD program at the University of Texas at Austin.

“When I became a teacher, I always tried to provide different perspectives in all the social studies courses that I taught, and then when I was getting my PhD, everything just started making sense,” said King. “I started to learn the history of Black history—something that we’ve been dealing with as a country since the 19th century. And while a lot of things have changed, a lot of things are still the same. So, I felt that my research needed to delve into Black history, and more broadly, I wanted to answer the question: What is Black history? Because we have not answered that question as a country.”

In graduate school, he read seminal texts on Black history, like “The Mis-Education of the Negro” by Carter Godwin Woodson. He studied slavery and oppression. The connections between these past events and the present notion of anti-Blackness in our society became clearer. And his passion for history—and desire to solidify the definition of Black history—grew. “History is not about patriotism. History is about helping us understand our humanity. That’s the good, the bad and the indifferent,” he said.

King’s career led him to Clemson University and the University of Missouri before arriving at UB. Throughout the journey, he has held tightly to his vision and goals—one way to carry them out: providing mentorship to students and educators.

Greg Simmons, doctoral student in the Department of Learning and Instruction, sought out King’s guidance while teaching Black history at Columbia Battle High School in Columbia, Missouri. After speaking to Simmons over the phone, King came to observe him in the classroom, gave him feedback and ultimately suggested that he explore transitioning to another teaching space to make a more significant impact.

From there, their relationship blossomed, and King became Simmons’ mentor. “When I talk to my fellow grad students, either at Mizzou or elsewhere, and I tell them how he is, they tell me I hit the lottery,” said Simmons. “With a lot of professors, our success as PhD students is tied in with their success. A lot of folks just focus on the academic part of the relationship, but LaGarrett is concerned about the whole person.”

Dawnavyn James echoes Simmons’ sentiments by explaining that King has shown her an example of how to support colleagues, students and the community. From her perspective, King is not only a lecturer but an opportunity creator. Once King discovered her interests, he consistently reached out with professional networking opportunities to advance her career growth. Now, she does the same for coworkers and friends. “He really values community and wants to help … and it’s genuine,” she said.

Greg Simmons and Dawnavyn James.

In addition to extending mentorship, King has carried out his mission through his research, including developing his Black historical consciousness principles. He felt compelled to create the framework because of the archetypal focus on oppression and liberation in Black history curriculum.

“People were always oppressed, but then they fought against that oppression. And they were always reactive instead of proactive. That’s the general sense of it. And then, sprinkled here and there, you learn about certain exceptional human beings,” he said.

“I wanted to come up with a Black history framework that school districts can utilize, to not only teach about oppression and liberation but also just teach about the humanity of Black people. Through researching Black history textbooks and Black history curriculum and reading about Black historians, I found that there are principles that schools and school systems need to realize when they are developing Black history curriculum.”

Through his framework, King aimed to break the mold of stale state curricula to help students, teachers and administrators realize a more robust depiction of Black history.

- Power and Oppression: Highlight the lack of justice, freedom, equality and equity that Black people experienced throughout history.

- Black Agency, Persistence and Perseverance: Explain how Black people fought and survive oppressive acts against them. These acts were proactive and reactive as well as aggressive and subversive.

- Africa and the African Diaspora: Stress that narratives of Black people are contextualized within the African Diaspora.

- Black Emotionality: Feature narratives of Black people and their various emotions including rage, joy, love, laughter and pleasure. These emotions define Black people's humanity and existence. These histories exist even in times of oppression.

- Black Identities: Depict a more inclusive history that seeks to uncover the multiple identities of Black people through Black history.

- Black Historical Contention: Recognize that all Black histories are not positive. Black histories are complex, and histories that are difficult should not be ignored.

- Black Community, Local and Social Histories: Teach Black history through regular persons who made a difference in their communities and state. This approach to history removes the messiah complex. It also identifies people who may not have been the most popular or respectable, but who fought for the everyday person.

- Black Futurism: Use lessons from Black histories to reimagine the contemporary and future.

Since its development, King’s framework has been featured in Education Week and scholarly journals, such as Urban Education and Race Ethnicity and Education. The principles have also been implemented in school districts in Kentucky, Missouri, Wisconsin, Michigan, Pennsylvania, Iowa, Ohio, Texas, New York and throughout Canada. These guidelines are intended to help all teachers, regardless of race or background. According to Simmons, he and King work well together because they share a pragmatic view of education. “We know white teachers are going to teach Black history, so we can either help them to do it well, or we can leave them alone and then it could go really poorly,” said Simmons. “It’s not a question of if white people should teach this; it’s a question of when. We think about things and develop pedagogical approaches to help support them in that work.”

King also offers support in his most recent book, “Teaching Enslavement in American History: Lesson Plans and Primary Sources,” co-authored with Dr. Chara Bohan and Dr. Robert Baker, both faculty at Georgia State University. Published in May 2022, the book provides lesson plans and guidance for educators navigating topics such as the middle passage, the Constitution’s position on enslavement, African cultural retention and resistance to enslavement.

As Rosenblith sees it, King has already advanced GSE’s equity, diversity, justice and inclusion efforts through his work and the center’s programming. “He is a great example of GSE’s commitment to public scholarship,” she said. “I think the mission of a school of education in an urban setting at a research-intensive university is to help improve the lives of individuals and communities through our research, teaching and engagement. And that’s exactly what he does.”

This summer, the center’s programming continues with its signature event, the Teaching Black History Conference. From July 22-24, hundreds of teachers will convene in Buffalo or virtually to learn about the best curricular and instructional practices surrounding Black history education. And everyone’s invited: community educators, parents, school-aged students, librarians, museum curators and history lovers.

This year’s theme is Mother Africa, sparked by King’s long-ago observation that children are first introduced to Black people in school through enslavement. “When we do that, we miss out on thousands of years of history, and there are implications to understanding Black people as ‘your slaves.’ But, if we understand them as different ethnic groups in Africa, you get to understand their humanity,” he said. “You get to understand various cultures. You get to understand how these particular people live. You get to really understand how they got to the Western world.”

The conference will feature elementary, middle and high school workshops as well as general, university and adult education sessions. The event will also focus on understanding the continent today: “It is not only just the mother and her children, right? The Caribbean, the U.S., the U.K.—All these places that Black people travel to throughout the diaspora are not simply based on slavery, but based on African explorations around the globe … All those things are extremely important for us to get back to where it all started so that we can get to the crux of humanity.”

Keynote speakers will include Joy Bivens, director of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture; Dr. Nwando Achebe, Jack and Margaret Sweet Endowed Professor of History at Michigan State University; Dr. Gloria Boutte, associate dean of diversity, equity, and inclusion and Carolina Distinguished Professor of Early Childhood Education at the University of South Carolina; and Dr. George Johnson, professor at South Carolina State University.

“So, these people who were newly ‘free’—and many were illiterate—decided to do two things: write history and right history.”

This spring, enthusiasm about the new center is palpable in GSE. With the center comes a new era in instruction as the university now is a hub for developing historically conscious and racially literate students, teachers and community members around the globe.

King is excited, too. His wife, Dr. Christina King—also a new faculty member in GSE’s Department of Learning and Instruction—and two children, Preston and Presley, join him on this new journey. They have begun exploring the intersection of Black and Buffalo histories by learning more about Buffalo’s Underground Railroad sites and public art projects, like the Freedom Wall (see below), which depicts historical figures who have fought for civil rights and social justice, including Rosa Parks, Malcolm X and W.E.B. Du Bois.

While he looks forward to his work as the director of the center and a social studies education associate professor, his passion extends further than formal roles. He is inspired by the past when extending mentorship and guidance that will impact future generations.

“I'm always standing on the shoulders of people, all the way back from the 19th century. They said, ‘when we got out of slavery to emancipation, we started Sunday schools. Literacy was one of the reasons why we started Sunday schools. And one of the things we picked for literacy was history books,’” he said. “So, these people who were newly ‘free’—and many were illiterate—decided to do two things: write history and right history. That, to me, is very inspirational. And I hope that I add just a little bit to their legacies moving forward.”

Located at the corner of Buffalo’s Michigan Avenue and East Ferry Street, the Freedom Wall depicts portraits of 28 prominent American civil rights leaders who have impacted our nation’s struggles for social and political equity. The mural was created in 2017 by Buffalo-based artists John Baker, Julia Bottoms-Douglas, Chuck Tingley and Edreys Wajed.

Through a partnership with the Albright-Knox Art Gallery Public Art Initiative, the Michigan Street African American Heritage Corridor and neighborhood stakeholders, the artists came together to celebrate and share the unique stories and histories of past and present leaders, such as W. E. B. Du Bois, Rosa Parks, Malcolm X, Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture), and King Peterson.

This project aims to encourage conversations about previous journeys toward equality and freedom and the actions that still must occur to create a just and equitable world.