campus news

Ukraine’s past, future dominates Distinguished Speakers Series lecture

During her appearance at UB, Marie Yovanovitch (right) answered questions posed by moderator Elena V. McLean (left), UB professor of political science, and audience members. Photo: Joe Cascio

By ANN WHITCHER GENTZKE

Published November 17, 2022

Her talk covered a range of topics related to American diplomacy, but Ukraine —its eventful past and precarious future —dominated Tuesday’s Distinguished Speakers Series address by Marie Yovanovitch, former U.S. ambassador to that beleaguered but proud nation.

Yovanovitch, who was abruptly recalled from her ambassadorial post in April 2019 and testified that November in the first Trump impeachment hearing, spoke of her upbringing by immigrant parents, along with key events in her 33-year career with the U.S. foreign service. Moderator Elena V. McLean, UB professor of political science, posed her own and audience questions before an appreciative audience in the Center for the Arts.

Yovanovitch was last in Ukraine this September, when she visited with Ukrainian leaders, and with friends and former colleagues in the U.S. diplomatic corps. She noted the courage, commitment and confidence of the Ukrainian people, even in the face of the “terrible missile attacks on civilian infrastructure and Ukrainian citizens” earlier this year. Yovanovitch said she believes Ukraine will ultimately prevail. But the U.S. will have to continue its support, both with weapons and diplomatically, she asserted.

For those who might wonder why we should care about Ukraine’s awful predicament, Yovanovitch said “it’s the right thing to do. Ukraine is a country of democracy; a struggling democracy, but nevertheless a democracy that was attacked without reason, for the second time, by its neighbor, a totalitarian state. And that is not in keeping with our values.”

Moreover, she argued, if Vladimir Putin is successful in a second war against Ukraine, “he will keep on rolling … and we will be foolish to ignore that. … What kind of a world will we be in where countries get to do whatever they want?”

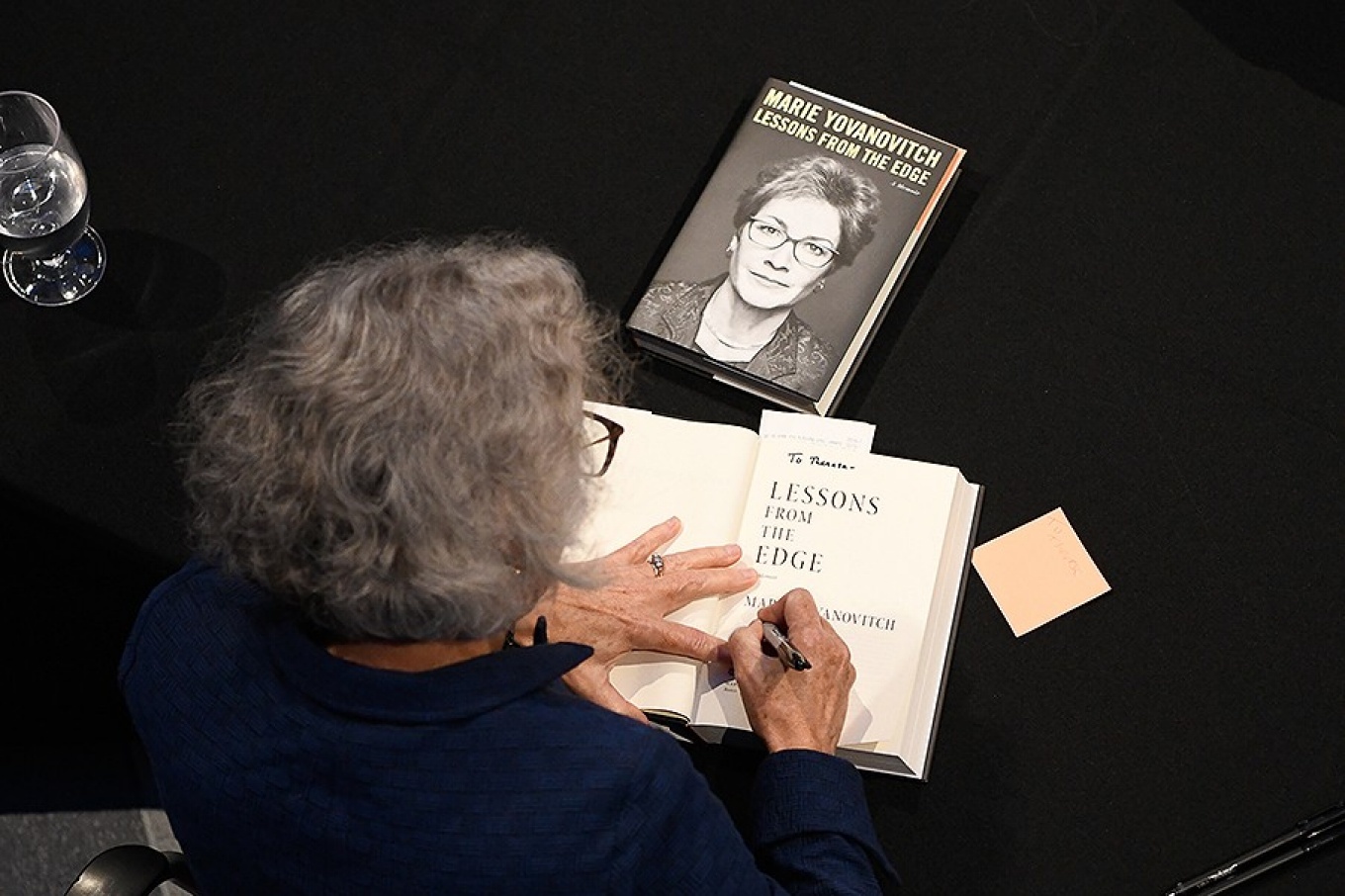

Following her talk, Marie Yovanovitch signed copies of her book in the Center for the Arts atrium. Photo: Joe Cascio

Asked if a diplomatic solution is in the offing, Yovanovitch said it’s possible, but not now. “On one hand, you have Russia, which is losing and digging in. On the other hand, you have Ukraine, which wants to press its advantage, because if it stops now for diplomatic talks, Russia will have an opportunity to do what it did back in the spring: to rest, regroup, rearm, recondition and attack. The Ukrainians are exhausted, as you can imagine. But they don't want to give that advantage to Russia.”

On the roots of her diplomatic career, Yovanovitch spoke movingly of her parents: her mother, Nadia, once stateless in Nazi Germany, and her father, Michel, of Russian-Serbian parentage who grew up in Yugoslavia and who had also been stateless after escaping from a Nazi POW camp. The couple met and married in Montreal, where Yovanovitch was born in 1958; the family then moved to Kent, Connecticut. Growing up, she and her brother were taught to appreciate the freedoms found in the U.S., and certainly not to take their liberties for granted, especially given her parents’ struggle for survival during World War II and its aftermath.

An interest in travel and other cultures was beginning to predict Yovanovitch’s career in foreign service following her graduation from Princeton University with a degree in history and Russian studies. She was working in a Manhattan advertising firm in 1983 when, riding the subway on her way to work, she read about the U.S. invasion of Grenada and wondered what factors had led to this event. That day at work, she and her colleagues were debating which color to use in a campaign layout when she realized, “This is not for me. I need to be working on the things that I’m most passionate about, like foreign policy.” She began the process of taking the difficult U.S. foreign service officer exam. It was hard, Yovanovitch said, and she failed the first time. But perseverance paid off, and she passed the second time, going on to hold a succession of overseas posts, including the Russia desk, before moving on to serve as U.S. ambassador to the Kyrgyz Republic and then Armenia, before taking up the top diplomatic position in Ukraine in 2016.

Marie Yovanovitch's bestselling memoir, “Marie Yovanovitch: Lessons from the Edge,” was published in March. Photo: Joe Cascio

Yovanovitch described the painful events of 2019, when she was summarily recalled from her post in Kyiv and testified about her ouster before Congress. She was sustained in this ordeal by the “hundreds, if not thousands” of letters of support she received from people all over the U.S., many of whom urged her to put her experiences in book form. Her bestselling memoir, “Marie Yovanovitch: Lessons from the Edge,” was published in March 2022. Having retired from government service in 2020, Yovanovitch is currently a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace and a non-resident fellow at the Institute for the Study of Diplomacy at Georgetown University.

In closing, Yovanovitch talked about the beautifully maintained garden terrace in the historic building in Kyiv where she worked. After a tough day, she would go there and contemplate the sight before her: a blend of nature and the gold cupola of a nearby church, illuminated at night. “It was so rejuvenating and gave me hope.”

She also described how about 800 people, mostly Ukrainians, had gathered for a Fourth of July reception in the garden in 2017. In the early 2000s, when Yovanovitch was deputy chief of mission in the U.S. embassy in Kyiv, Ukraine was still in search of an identity, she said, and few seemed to know the lyrics of Ukraine’s national anthem. But in 2017, the Ukrainians assembled in the garden sang the anthem robustly with all the words intact.

“Ukraine was born as a nation,” Yovanovitch recalled.

Following the lecture, Yovanovitch signed copies of her book in the Center for the Arts atrium.