Q&A

First solo museum exhibit explores 'underloved,' overlooked historical narratives

By VICKY SANTOS

Published March 6, 2025

Photo: Brandon Watson

UB faculty member Crystal Z Campbell’s first solo museum exhibit, “Currents 124,” is currently on display through March 9 in the Saint Louis Art Museum. The multidisciplinary exhibit explores Campbell’s recent works using “underloved” and overlooked historical narratives, particularly those tied to U.S. colonialism in the Philippines, which is influenced by Campbell’s Black, Chinese and Filipinx heritage.

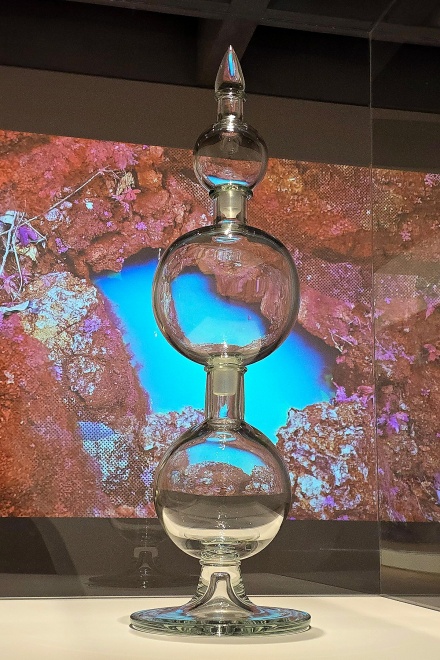

Campbell’s work blends archival interventions, abstraction and material histories. A key feature is a series of blown-glass apothecary vessels — created at the Museum of Glass in Tacoma, Washington —symbolizing healing from colonial legacies. These themes connect to the history of St. Louis, where more than 1,200 Filipinos were brought to the 1904 World’s Fair there as living exhibits, with many succumbing to disease.

Campbell’s paper works, made from manila envelopes and rope during a fellowship at Dieu Donné, reference the Philippine abaca industry’s colonial ties. A video installation, “Makahiya,” explores nature, colonization and abstraction.

“I’m deeply attuned to notions of the archive and public memory, and this show marks an expansion in my practice from predominantly video/film installations to include works in glass, as well as handmade paper works,” says Campbell visiting associate professor in the departments of Art and Media Study.

Campbell, the 2023-24 Henry L. and Natalie E. Freund Fellow, developed this exhibition during a residency at Washington University’s Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts. It is part of the museum’s Currents series highlighting emerging and mid-career artists.

Campbell spoke with UBNow about the archival investigations, embodied experience and material history that informs their creative research.

Can you talk about working with the Saint Louis Art Museum and how your exhibit there came to fruition, and how it ties in with your ongoing project, “Post Masters?”

My mother, who is Filipinx and Chinese, hails from Manila, Philippines, and my father is a Black man from Missouri. They met while my father was in the military. Later, they both ended up working for the U.S. Post Office, as did I for a summer. Envelopes and mail are a critical part of my formative years but also the formative years of this nation. I’ve been thinking about how Benjamin Franklin, the first U.S. postmaster, used his position to forge a U.S. identity through the dissemination of mail, roads and infrastructure, and banal nationalism such as stamps. After the Spanish American War, the U.S. expanded its empire into Guam, Puerto Rico, Hawaii, Cuba and the Philippines. “Post Masters” is an excuse to think through the material and archival traces of U.S. colonialism in the Philippines through post masters. My personhood is a direct result of the overlapping arms of empire and colonialism, but also, love.

A view of Crystal Z Campbell’s installation at the Saint Louis Art Museum. This image features the handmade paper works Campbell created in collaboration with Tatiana Ginsberg at Dieu Donné Papermaking Studio. 2024. Photo: Saint Louis Art Museum.

As the recipient of a Henry L. and Natalie E. Freund Teaching Fellowship, how has your time in St. Louis and at the Sam Fox School influenced your artistic practice and this body of work? What drew you to this theme? And why was the history of the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition and its impact on Filipinos important to include in this exhibit?

I applied to the Freund Fellowship several years ago, intrigued by the two-fold possibility of designing and teaching a new course at Washington University and a solo exhibition at the Saint Louis Art Museum. I developed my dream course, Artists in the Archive, and taught it when I returned to UB. Visiting the UB medical archives with Dr. Keith Mages, curator, History of Medicine Collection, spawned my interest in the glass show globes that were used to attract non-literate people to apothecaries (which precede modern day pharmacies). A residency at the Museum of Glass gave me access to an expert team of glassblowers, who manifested these giant, tiered, blown-glass apothecary vessels based on drawings I shared.

Part of my proposal for the Freund fellowship was implicating the context of the Saint Louis Art Museum, which was built as part of the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition — commonly called the St. Louis World’s Fair. This world’s fair devoted the largest amount of its exhibition space to show off its recent colony: the Philippines. Over 1,200 Indigenous Filipinos were brought over and forced to construct Indigenous architecture and perform rituals in front of a hungry audience like a living zoo. Many Filipinos died from diseases transmitted through this colonial encounter in the U.S. While many Filipinos in the present-day U.S. work in the nursing or care industries, it was critical to bring in symbolism for potential healing through these apothecary vessels upon this site, whose very architecture is an inadvertent monument of this complicated exposition.

Blown glass is an important feature of Crystal Z Campbell’s exhibit at the Saint Louis Art Museum. This image features Bukang Liwayway (blown glass made with Museum of Glass) and “Makahiya” (film still). 2024. Photo: Crystal Z Campbell

This exhibition explores overlooked historical narratives and the concept of the “underloved.” The use of manila envelopes and rope in your papermaking pieces directly references the Philippine abaca industry under U.S. colonial rule. How do material choices shape the storytelling in your work?

For the last several years, I’ve been framing my creative practice as one that centers the underloved or people, places, things and histories that I would like to amplify and divert more attention to. During my residency at the papermaking studio, Dieu Donné, I’ve been working with renowned papermaker Tatiana Ginsberg. I found that almost 80% of the world’s abaca is produced by the Philippines, and the industry was seized by the U.S. during colonial rule. Tatiana shared some of the raw abaca the studio had, and I was immediately attracted to it because it was unruly, but there was also this hairlike structure from the abaca being combed. I began enveloping the abaca into these abstract compositions meshed with abaca paper, manila envelopes and manila rope. Manila rope from the maritime industry was upcycled into abaca paper once the rope broke down, almost like a weathering process. But manila envelopes no longer use abaca, so the name is a specter of this colonial history. Manila envelopes were used to transmit important information, but they were never meant to be looked at. I’ve been synthesizing these iterations of the material by an enveloping process that functiona like abstract painting or archaeological displays. It’s a way of honoring this history of the courier — my mother delivered mail — and carrier.

Where might the UB community be able to see your work next? What’s on the horizon for your next exhibit or body of work?

I have some upcoming film screenings and museum exhibits elsewhere, and in Buffalo, I am finishing the preparations for an upcoming group show at Squeaky Wheel in March and a newly commissioned video projection at the historical grain silos with Just Buffalo Literary Center this summer.