Unraveling the complexities of literacy education

UB’s comprehensive approaches are reshaping literacy education, fostering community partnerships, and preparing future literacy professionals to tackle educational challenges

BY ANN WHITCHER-GENTZKE

Unraveling the intricacies of learning to read and write requires persistence, patience and unyielding curiosity—all qualities of the committed scientist intent on discovery.

Researchers in the Department of Learning and Instruction display these characteristics as they study methods to bolster children’s literacy achievement and understand its many facets. In their quest, they draw on GSE’s decades-long tradition of researching this critical issue, reaching out to the community with well-tested programs at the Center for Literacy and Reading Instruction (CLaRI), now celebrating its 60th anniversary. Other educational initiatives involve the direct application of faculty research via partnerships with school districts in Western New York, across the state and in other states, too. Meanwhile, GSE’s literacy faculty, many of them former K-12 teachers, are equipping teachers and literacy specialists with the tools they’ll need to help children grow as readers, and to become literate in every sense of the word.

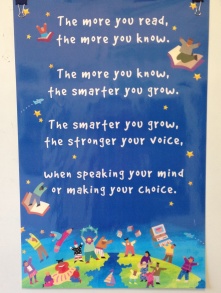

Walking into CLaRI in Baldy Hall, visitors spot colorful posters and engaging materials encouraging kids to embrace reading. A flyer in the waiting room, illustrated with children from different nations atop the globe beneath a starry sky, promotes reading as empowerment with a simple rhyme: “The more you read, the more you know. The more you know, the smarter you grow. The smarter you grow, the stronger your voice. When speaking your mind or making your choice.” Within the suite are personalized tutoring areas for each child and a library of children’s books that they can check out for home reading.

Ashlee Campbell, associate director of CLaRI and clinical assistant professor in the Department of Learning and Instruction

Ashlee Campbell, associate director of CLaRI and clinical assistant professor in the Department of Learning and Instruction, has day-to-day responsibility for individualized programs for children who are reading below grade level. Tutoring includes after-school sessions twice a week during the academic year, Saturday morning tutoring, a one-on-one tutoring program during the summer, and a summer reading camp.

Each academic year, CLaRI serves 25 to 30 students in the fall and spring semesters, and about 60 students during the summer. Twenty to 30 students participate in CLaRI’s free summer camp, where graduate students in the literacy specialist program provide all the instruction. “Summer programs have become the most popular because parents want their children to engage with reading and writing over the summer,” said Campbell. “Other families seek summer tutoring to help develop their child’s overall literacy abilities. CLaRI, as a research center in the University at Buffalo’s Graduate School of Education, may offer financial assistance to families according to need, so that children can attend and receive the literacy support they need. Virtual tutoring is offered as well.”

The CLaRI after-school tutoring program is a “special place” where both children and adults have roles as learners, Campbell said. Tutors in this program are UB graduate students who are also certified teachers pursuing master’s degrees with professional certification as New York State literacy specialists.

Campbell supports these teachers' development by introducing them to the well-known literacy model of gradual release of responsibility, along with evidence-based instructional approaches. She carefully reviews each tutor’s lesson plan before teaching, while also providing guidance in “critical video reflection,” a long-time CLaRI practice described in a book by current and former UB literacy faculty. “The teachers record each session and later review the video to reflect on their literacy instruction and on the child’s learning,” Campbell explained. “This helps teachers become reflective practitioners who think critically about instruction and keep student learning at the center of instruction.”

Campbell also debriefs each teacher after tutoring to discuss the next logical steps for instruction. The graduate student teachers follow a diagnostic teaching model that requires informal assessments of a child’s progress. This could come in the form of anecdotal notes or word sorts that help children identify certain orthographic patterns, or through formal assessments. Furthermore, Campbell lets graduate students know that a clear evidence-based purpose must be shown. If this doesn’t occur, she might ask, “What did the child do during the last session that supports this [next] lesson?” In this way, instruction is tailored to meet each child’s literacy and learning needs, and also helps develop the graduate student’s ability to implement literacy practices. In the end, there are many success stories.

Ashlee Campbell outlines the day's agenda at the end-of-tutoring celebration at CLaRI, where students showcased their work and received certificates of achievement.

Parents usually find out about CLaRI programs from recommendations of friends or relatives whose children have attended past sessions. Leisanne Smeadala learned from her sister how helpful CLaRI could be to children having reading difficulties. So, she enrolled her daughter, Nora, now in first grade. “Our experience has been great,” Smeadala said. “Nora loves going, and her reading is definitely progressing in ways that I don’t think it would be if she weren’t attending. She needs additional reading support and opportunities to practice. I had the opportunity to experience a session recently due to the use of Zoom, and I was impressed with how well the teachers handled Nora’s tutoring.”

The CLaRI after-school tutoring program is a “special place” where both children and adults have roles as learners.

Sherry Arndt, parent of a third grader, expressed similar sentiments about the progress her daughter has made since attending the summer reading camp and with ongoing tutoring since. “My daughter is about six months behind in her reading, but she’s on track with other courses. I believe it is vital for her to continue in a reading program throughout the summer months. The CLaRI program has been able to fill this gap and improve upon the skills she is gaining during the school year.”

Another testimonial points to CLaRI’s impact on children with difficult personal circumstances. Angela Hester is a foster mom of three kids, two six-year-old boys in first grade and an 8-year-old girl in second grade. They come to CLaRI for tutoring; they have also attended summer camp. “My children were at least two grade levels behind in reading,” Hester said. “My 8-year-old girl could not even identify letters. Now she is reading three-letter words, and the boys are approaching grade level. I am so proud of their hard work. They love attending the reading program.”

John Strong, assistant professor of literacy education

As CLaRI moves into its 61st year, GSE faculty and students eagerly await the school’s scheduled move to Foster Hall on UB’s South Campus in 2025. The move promises increased connection with the Western New York community in conjunction with the goal of raising reading achievement among area schoolchildren. “At this point, it is all private transportation to get to CLaRI,” said Campbell. “However, with the move to the South Campus, while we won’t offer busing, we will have the metro right there. This will allow more families who live farther away, or who don’t have a lot of transportation options, to take the bus or metro to get here.” Mary McVee, CLaRI director, agrees that the new location will make the center more accessible to a broader community. “I remember a grandmother who took two or three buses to bring her grandson here,” she said. “But that’s really hard on families.”

While access to CLaRI stands to improve with the impending move to South Campus, researchers in the GSE argue that unless practitioners and schools take a comprehensive approach to literacy instruction, many students will still be at a disadvantage.

Research shows that literacy today and in the future is increasingly complex. It includes proficiency with digital and visual media, as well as the language of specific fields like STEM subjects. There is also ongoing interest in the cultural and racial literacies needed to support a diverse democratic society. However, the traditional understanding of literacy as the ability to read and write competently remains a topic of significant debate among educators, politicians, and citizens concerned about children's literacy rates nationwide and in New York State.

The picture has been concerning for some time. “When we look at national assessments of children’s educational progress, two-thirds of children are comprehending below a proficient level,” said John Strong, assistant professor of literacy education. “It’s been that way since the 1970s, when the federal government began conducting the NAEP, the National Assessment of Educational Progress. It’s not a new problem; it’s an unfortunate problem.”

This year, New York Gov. Kathy Hochul, alarmed at post-pandemic reading rates among the state’s third graders (fewer than half of whom were proficient in statewide testing in 2023), called on school districts to implement “scientifically proven” methods for teaching literacy to New York’s schoolchildren. Hochul proposed $10 million in funding, specifically calling for programs in SUNY and CUNY to take on the teacher training necessary for this ambitious endeavor. But GSE experts say such an approach isn’t sure-fire without improvements in the research-practice divide, and more evidence-based teaching methods delivered to New York classrooms and beyond.

Often the implementation of the “science of reading” has been to replace prior methods of teaching reading with evidence-based approaches that primarily involve an increased attention to phonics. A problem arises, however, when these newer methods are introduced in classrooms without thorough testing of, or research into, their efficacy. Strong deems this process vital to improving reading education and ultimately to raising literacy rates. “I think a lot of schools and districts in recent years have said, ‘We’re moving to the science of reading.’ What they mean is they’re moving away from programs they have used previously and adopting a different program. You’ll find New York City has mandated curricular programs, for instance. But none of them are the subject of experimental studies either. So, while they claim to be ‘science of reading’ approaches, unless they’re tested in experimental studies, we don’t actually know if they work to improve kids’ outcomes.”

Strong’s own research includes a paper published last year in Scientific Studies of Reading, with co-authors Henry May and Sharon Walpole. They found increased reading achievement among children in grades 2-5 who were taught using the Bookworms literacy curriculum. Strong reports that the study “was able to actually model what children’s reading growth would continue to look like had they not adopted Bookworms versus what it did look like when they did adopt it. We found positive effects on literacy achievement using the standardized Measure of Academic Progress.”

“When we look at national assessments of children’s educational progress, two-thirds of children are comprehending below a proficient level.”

Such results don’t constitute a panacea, Strong cautioned. “It’s not a magic bullet: Kids get Bookworms and next week, they’re readers. But this was nearly 10,000 students in a school district over several years. We can see that Bookworms had an effect on their achievement—it was slow at first and then it became faster. It demonstrates the cumulative effects over time of high-quality instructional practices such as lots of high-volume book reading. You have to read books to get better at reading. There’s no way around it, and most curricular programs don’t have kids reading a whole lot of books.” Strong contrasted “controlled” reading often found in curricular texts used in schools with “authentic” materials, defined as actual books written for children.

While earning his doctorate at the University of Delaware, John Strong researched and designed interventions for student learning that teachers could use in the classroom. At UB, the former high school English teacher has continued to investigate research-based programs to help K-12 teachers foster literacy among their students. Like many of his colleagues, Strong is deeply involved with the community, for example, leading recent professional development sessions in evidenced-based literacy instruction for district assistant superintendents and literacy coordinators under the auspices of Erie I BOCES with his colleague Blythe Anderson. He’s also principal investigator for a $300,000 grant from the Advanced Education Research and Development Fund to study an intervention program he developed, Read STOP Write. (STOP stands for “Summarize, Text structure, Organize, Plan.”) A revised edition of this program he developed with colleagues at UB and Michigan State University is now being implemented in several schools in Western New York and Michigan.

For Strong, a scientific basis for reading education is paramount. Too often, he says, school districts adopt programs from commercial publishers that haven’t been reliably tested or examined in experimental studies. “The science of reading is not an approach, a program or practice,” he said. “It refers to the body of scientific research on how children read and how to most effectively teach children how to read. There are many different types of research—qualitative, quantitative, correlational, experimental. But I choose to focus my work on experimental research.”

Blythe Anderson, assistant professor of literacy education

Blythe Anderson, assistant professor of literacy education, concentrates her research on instructional practices and curricular materials that promote vocabulary development. “Vocabulary is largely missing from the conversation on ‘the science of reading,’” said Anderson, a former first-grade teacher who was previously PreK-12 district literacy coordinator in Rochester, Minnesota. “We know there’s a ton of evidence for the importance of vocabulary. … Unfortunately, comparatively little time is spent developing vocabulary in the classroom.” Anderson elaborates that an emphasis on building foundational skills like phonemic awareness and word recognition “tends to crowd out vocabulary instruction, despite the supportive role that word knowledge plays in word recognition. There’s a critical need for integrated approaches to vocabulary instruction that build vocabulary knowledge concurrently with other foundational skills,” she said.

In a study published in the Journal of Literacy Research and The Reading Teacher, Anderson and colleagues identified specific vocabulary “talk moves,” or ways of using language to promote vocabulary development, that are aligned with the research on how children learn words. This study took place during science instruction, which offers an especially rich context for word learning.

“How can we support students in becoming word learners and get them really curious and interested in learning words?” Anderson asked. “There’s something called word consciousness that I’m really interested in. It’s mostly theoretical at this point, but there’s an idea that we can support kids in becoming really curious about words and interested in learning words, and this will support them in engaging with words and being motivated to tune in to words when they come across them.”

She adds: “When people think vocabulary, I think most of the time they’re thinking about its relationship to reading comprehension. ‘If you understand the meanings of the words, you’re going to have a better time understanding the meaning of the text itself.’ That makes sense. But vocabulary knowledge also works the other way; it bridges toward word recognition. So there are studies that have shown that our vocabulary knowledge actually supports us with decoding. If it’s a word that you know in your oral language, you have a better chance of decoding that word, even if you’ve never seen it before.”

As do her GSE colleagues in literacy education, Anderson delivers research with a strong community impact. In a study published in Reading & Writing Quarterly, she and John Strong examined the effectiveness of a summer reading program for children in kindergarten through fifth grade, in which graduate student tutors delivered 15 minutes of “differentiated reading instruction” and a 30-minute interactive read-aloud to small groups of students each day. She’s also a co-principal investigator of the Read STOP Write project which entails frequent contact and involvement with teachers and their students. “We do a lot of modeling of Read STOP Write with the teachers who are participating in the study … We’re in schools all the time doing professional learning sessions for teachers and working with their students.”

Kristin Overholt, assistant superintendent for curriculum and instruction in the Clarence Central School District, is among those who’ve worked with GSE faculty to incorporate research into the public school landscape. “The partnership with the University at Buffalo has further enhanced the structured literacy approach in the Clarence School District,” she said. “Leveraging evidence and research-based methodologies and professional development opportunities, teachers are equipped with cutting-edge strategies to effectively implement structured literacy practices, resulting in even greater student success and academic growth.”

A number of partnerships exist with area school districts, either through a formal agreement, or through the lessons brought back to classrooms via alumni of GSE’s literacy education degree and certificate programs. David Fronczak had already worked as a teacher and literacy specialist when he returned to UB as PhD student in the Department of Learning and Instruction. In support of his doctoral studies, he is the recipient of the scholarship named for William Eller, CLaRI’s founder and first director. “I am filled with gratitude to return to the University at Buffalo Graduate School of Education as a PhD student following the completion of the Literacy Specialist EdM here in 2014. Serving as a graduate assistant, I have the invaluable opportunity to collaborate with distinguished reading researchers who dedicate themselves to making a positive impact in students’ and teachers’ lives through their scholarship and partnerships with local schools. Engaging with students and educators throughout Buffalo has been immensely rewarding.”

Mary McVee, professor of learning and instruction, and current CLaRI director

Since arriving at UB in 2000, Mary McVee, professor of learning and instruction, and the third, and current, CLaRI director, has seen significant changes in literacy education. These include different terms to express key concepts (reading specialists versus literacy specialists, for example), greater interest in multilingual learners, and concerns over the science of reading. There have also been conceptual shifts that reflect a widening field of literacy inquiry. One such shift is “the modal turn.”

“Instead of just thinking about literacy as reading or writing print text and working with words, the ‘modal turn’ is the idea that literacy includes working across lots of modes, especially when we think about digital media,” explained McVee, a former ESL teacher who earned her PhD at Michigan State University. As principal investigator of a three-year, $375,000 grant from the National Science Foundation, she is researching how elementary school teachers can best approach engineering instruction for their multilingual elementary school students.

McVee, in her work on the NSF grant, with co-principal investigator Jessica Swenson, assistant professor in the UB School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, is keenly aware that teachers have a lot on their plates nowadays, given the impact of changing mandates and standards, and a student population that’s increasingly multilingual. “We’re trying to help develop a professional learning model where we bring teachers together and help them think about the language and literacies for those students who may be emergent bilinguals, or who may be further along in their language journey into English,” McVee explained.

“We’re also thinking about how teachers position themselves with relation to their views of language. How do they then introduce different types of language and literacy activities in the classroom?” As part of the grant, teachers from Amherst and Sweet Home Central School Districts began meeting in the fall at CLaRI. “We’ve done engineering activities with them here, as well as talked about translanguaging, a term that means allowing students to draw on all of their repertoires of language. …We’ve worked with the teachers as well on discussions and readings related to the topics of literacy and disciplinary literacy.” In future years, she said, teachers will also engage in reflection on their teaching using video, linking into another CLaRI tradition.

“We’re trying to help develop a professional learning model where we bring teachers together and help them think about the language and literacies for those students who may be emergent bilinguals, or who may be further along in their language journey into English.”

Reflecting on her own work and that of her colleagues, McVee points to the essential unity of GSE’s various approaches to literacy, notwithstanding the many vistas faculty are exploring. “If we can enable emergent bilingual students to learn some of the content as they’re going along, they will feel like they’re really members of the community that is helping them. It will help them in their overall learning, too. And if a parent comes to CLaRI and they’re concerned that the child isn’t reading at grade level, or they’ve been told the child is behind on a progress marker,” all this matters, she said. “So we need interventions like the work John Strong and Blythe Anderson are doing, and what Ashlee Campbell is helping us do here with the children in CLaRI as well.

“It’s definitely not about one thing or the other,” she concluded. Rather, it’s a panoply of thoughtful—and tested—approaches for resolving the literacy conundrum.

CLaRI: A 60-year Legacy

Discover the rich legacy of literacy education at UB. Dive into the inspiring stories of pioneers like William Eller, Michael Kibby, and Sam Weintraub, whose groundbreaking work in reading instruction has shaped generations of educators and students. From the founding of the CLaRI center to the ongoing impact of their innovative teaching methods, learn how their dedication and research have transformed lives. Plus, read about the enduring influence of alumna Jill Fitzgerald and her tribute to her mentors through the Drs. Sam Weintraub and Michael Kibby Fellowship Endowment Fund. Read more about CLaRI's history

Cover Story

UB’s comprehensive approaches are reshaping literacy education, fostering community partnerships, and preparing future literacy professionals to tackle educational challenges.