Where promise meets partnership:

UB and Buffalo Public Schools launch Buffalo’s first university-assisted high school

BY DANIELLE LEGARE

The school hallways in West Philadelphia were alive with possibility. GSE faculty walked alongside Buffalo Public Schools (BPS) leaders, observing classrooms where university partnerships had redefined what learning looked like. After-school projects buzzed with energy. Students were working side by side with Penn undergraduates, tending school gardens, experimenting with physics and even launching entrepreneurship clubs.

Angela Cullen, principal of Research Laboratory High School

Angela Cullen, principal of BPS’s Research Laboratory High School for Bioinformatics & Life Sciences, and Kira Mioducki, Research Laboratory’s science program coordinator, joined GSE faculty on a trip to the University of Pennsylvania’s Netter Center, where they saw firsthand how university partnerships could reshape learning in K-12 education.

For both the GSE and BPS leaders, the experience offered a glimpse of what could be realized closer to home.

“We were able to hear from districts that had tried different approaches to learning,” said Cullen. “It helped us see what had worked and what hadn’t, and to really strategize the direction we wanted to go in our school.”

GSE faculty Kristin Cipollone, Tim Monreal, Chris Proctor and Alexa Schindel felt the same way as they considered the path forward as leaders from the university embarking on a new partnership with BPS.

“We all recognized that this was uncharted territory. This has potential. This is something people are excited about. We can do this,” recalled Proctor, assistant professor of learning sciences and lead for the GSE team.

That trip to the University of Pennsylvania’s Netter Center was a turning point for GSE and BPS, who have come together to open Buffalo’s first university-assisted community school (UACS) this fall. But the groundwork had been laid years earlier.

The idea for a school focused on research traces back to UB’s Genome Day event in 2015, when nearly 400 BPS students visited UB’s Center of Excellence in Bioinformatics and Life Sciences to extract their own DNA and experience scientific research firsthand.

“Dr. David Mauricio, with Buffalo Public Schools, was inspired by the energy of the event and wanted to develop a school focused on scientific research that was co-located on the Buffalo Niagara Medical Campus or UB’s South Campus,” said Sandra Small, science education coordinator at UB, who served on the planning committee. “While we were not able to find a suitable space for a school on either campus, the committee moved forward with the concept and opened Research Laboratory High School in 2016.”

That early work laid the foundation for later conversations about a UACS model.

A few years later, BPS leaders approached GSE Dean and Professor Suzanne Rosenblith with the idea of a co-located “boutique” high school with a specialized curriculum. The timing wasn’t right, but the vision stuck with her. With encouragement from UB’s Provost A. Scott Weber, she began exploring the idea of a UACS, modeled after Penn’s Netter Center. She secured resources to bring the Netter team to Buffalo for a series of talks and focus groups, ensuring that faculty and leaders across the university could weigh in.

“The conclusion was clear,” Rosenblith said. “This is exactly in UB’s wheelhouse.”

When the district was ready to move forward, UB was too. A plan was waiting on the shelf, consensus was in place and the partners were prepared to act.

The question then became: Where should the partnership begin? With about 200 students and a home in the Tri-Main Center, Research Laboratory High School emerged as the ideal site. The school had longstanding ties with UB’s Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences through its earlier emphasis on sciences and was located near GSE’s soon-to-be new home on UB’s South Campus. Its leadership team, led by Cullen, was recognized for creative problem-solving and strong outcomes, including a 90% graduation rate.

“It just felt obvious,” Rosenblith said. “Why wouldn’t a university, with all of its resources and talents, partner with a school to do something innovative that benefits both students and the community where the university exists?”

Founded in 1992, the Barbara and Edward Netter Center for Community Partnerships at the University of Pennsylvania is considered the birthplace of the UACS model. Its core idea is straightforward yet radical: Universities bring their resources—academic, cultural and economic—into public schools, helping them serve not only students but also families and neighborhoods.

Unlike traditional partnerships, UACS emphasizes mutual benefit. It isn’t about universities “fixing” schools. Instead, the model centers on building sustained, democratic relationships where everyone is both a learner and a contributor, echoing John Dewey’s vision of schools as social centers and anchors for democracy.

At Penn, the Netter Center now operates across multiple schools in West Philadelphia, linking university courses and research with community problem-solving. Each year, roughly 90 courses connect more than 1,800 Penn students to local classrooms. The impact has been profound: improved student learning, stronger neighborhoods and a national network of universities inspired to follow the model.

“If we want a truly democratic society, we need institutions that help structure and sustain it. Schools and universities are central to that,” said Chris Proctor. “That’s the big vision: How can UB fulfill its broadest mission of serving the people of New York by partnering more deeply with a school? Like so many great research universities, UB isn’t yet as embedded in its community as it could be. This is a chance to change that.”

Inspiration meets action in Buffalo

Rosenblith saw a chance not just to co-design a boutique school, as BPS had first proposed, but to reimagine what a public high school without selective admissions—a true non-criterion school—could be. “I wanted this school to be computer science–infused,” Rosenblith explained. “The state had just passed new computer science standards, but there wasn’t much conversation about how to implement them. And Chris Proctor’s research convinced me that the best way wasn’t through a stand-alone class, but by infusing computational thinking into the core curriculum.”

That decision set the tone for the partnership between BPS and GSE. They had to be bold enough to try something new, while also remaining grounded in research and responsive to state standards.

“We’re fully hoping to be wildly successful and also understand that we might fail in some places and have to adjust,” she said. “Buffalo was on board with this. That was a huge game changer.”

“I really must credit Will Keresztes, who was interim superintendent at BPS,” Rosenblith continued. “He’s been really savvy about new initiatives. He knows the hardest iteration is always the first, so you have to set yourself up for success by choosing the right school and the right leaders.”

That same principle applied at UB. Rosenblith emphasized that building the right team was crucial to making the vision a reality. “Working with Angela Cullen and Karen Murray [BPS associate superintendent of school leadership] has made it so easy,” she said. “And when it came to the GSE team, I picked Chris Proctor, Kristin Cipollone, Tim Monreal and Alexa Schindel strategically because I knew they would be good partners.”

Designing side by side

For faculty like Proctor, whom Rosenblith tapped to lead UB’s side of the project, Research Lab offered the chance to realize something he had long imagined. “I’ve always had a secret dream of starting a school someday,” he said. “This gets pretty close.”

But it wasn’t about one person or group leading. Instead, Proctor was focused on building trust across UB and BPS.

“In the beginning, it felt like UB and Research Lab were on separate sides,” said Cipollone, clinical assistant professor of learning and instruction. “But the trip to the Netter Center and meetings after solidified the relationship. Everyone was serious, showing up for each other, invested in this together.”

Their conversations also clarified what was most important to both GSE and BPS. “For all of us, the priority is meeting the needs of Buffalo Public Schools and Research Lab,” said Monreal, assistant professor of learning and instruction. “That’s where the impact has to start.”

With BPS and GSE on the same page, the group settled on four key commitments to shape Research Lab’s next chapter.

Christopher Proctor, Tim Monreal, Kristin Cipollone, Kate Steilen, Kira Mioducki and Angela Cullen meet to discuss plans for the university-assisted community school partnership at Research Laboratory High School.

First was the importance of relationships. The teams agreed that they wanted to ensure that every student would be supported and connected to mentors at UB and in the community through advisory groups, restorative circles and internships. Cullen envisioned expanding hands-on opportunities far beyond science labs—from journalism to photography and more—while ensuring they remained paid experiences for students. “Ultimately, the biggest goal,” she said, “is that our students choose to enroll at UB, come back to Buffalo and give back to the community.”

Just as central was the belief in authentic inquiry and democratic decision-making. Students wouldn’t just learn about problems in their community. They’d investigate them, collaborate on solutions and present their work at a public symposium.

This belief resonates deeply with Schindel, associate professor of learning and instruction. She views the school itself as a place where structures and decision-making processes must be open, and where students and teachers have a genuine say in shaping after-school programs, the questions driving classroom projects and even the problems the school addresses. “That kind of engagement is itself a form of democratic practice,” she explained.

“If I were a part of a school that was involved in this,” Schindel continued, “I probably wouldn’t have left teaching. To actually be a part of something so dynamic and enriching intellectually for the whole community is just really exceptional.”

Another cornerstone was computer science as a connector.

Proctor’s passion and the team’s vision for the computer science curriculum go beyond job skills. A former English teacher, he compares coding to literacy. “Reading and writing let us reflect on who we are, to look back on how we were feeling at another time, to use words as a tool for thinking,” he explained. “Computers work that way, too. They help us model action and systems, connect ideas across subjects and use technology as a medium for thought.”

His perspective has practical implications at Research Lab. Every student will take computer science in 10th grade. From there, they will continue applying those skills through research projects and have the option to deepen their studies with AP courses or dual enrollment at UB.

Finally, the team saw the school itself as a living lab that would link UB courses and research with high school learning. Teachers would co-plan with UB faculty, students would apprentice in UB labs and university courses would be geared toward community needs.

Cullen hopes to take it even further by inviting UB professors to co-teach alongside BPS teachers, and by bringing undergraduate and graduate students into classrooms for short units and mini-lessons.

“The goal would be that our students develop those near-peer relationships,” she explained.

“They would see kids that look like them—students not that much older than them—coming in to co-teach with their Buffalo teacher,” Cullen said. “Our students would benefit from those relationships, while UB students would have the chance to give back to the community and possibly earn community service hours toward their degree.”

This emphasis on connections between UB and BPS is part of what makes Research Lab a model UACS, said Wil Green, GSE assistant dean of outreach and community engagement.

“One benefit of university-assisted community school partnerships is that pathways to higher education and careers are opened by connecting students directly to university faculty, resources, mentorship and programs. That access is critical, but the benefit of the partnership extends beyond favorable outcomes for students,” he said. “This work is more than a school–university partnership; it is about Buffalo itself. By aligning resources and expertise, we are helping to create stronger schools, stronger neighborhoods and a stronger city.”

Proctor hopes the curriculum and experiences will allow Research Lab students to reflect and ask themselves: “Am I the sort of person who can go to UB? Well, obviously I am, because I’m already taking UB courses,” he said. “And then that’s an opportunity to help UB transform itself, too, and ask itself inwardly, ‘Are we ready to meet the needs of these students? And if we’re not, let’s go, because these are the people we should be serving.’”

Early impressions at Research Lab

Kira Mioducki, who has served as science program coordinator since Research Lab’s opening in 2016, was quick to embrace the new partnership. Over the years, she has helped guide the school through relocations, shifting schedules and pandemic disruptions. That breadth of experience, paired with the relationships she’s built with administrators, teachers, students and community partners, has made her a trusted voice at Research Lab.

“At Research Lab, we stand with our ideas, not pushing them forward without walking alongside them, continually reflecting on how they reach our students and community,” she said.

Now, what excites Mioducki most about the shift is the chance to deepen the school’s reach while staying true to the culture that Research Lab has built over the years. She expressed that she sees the UB partnership as a chance to expand opportunities for both students and staff, while also giving the university a richer understanding of the community it serves.

Karen Murray, associate superintendent of school leadership, calls the partnership a milestone for the district.

“The fact that UB chose Research Lab … just think about the opportunities,” she said. “It’s not just for students, but for teachers, too. If we have a vacancy or a long-term sub, UB professors can step in with content knowledge. And when interns or professors see talented kids in action, they can connect families to new possibilities. We’re so happy about what this will bring our students, staff and families.”

Sandra Small, science education coordinator at UB, echoed that sense of possibility. “I’m excited to have this relationship grow into a formal partnership and take steps toward the school being co-located on UB’s campus,” she said. “Broadening this relationship to include research opportunities beyond science will give students the chance to explore projects in the humanities.”

“At Research Lab, we stand with our ideas, not pushing them forward without walking alongside them, continually reflecting on how they reach our students and community.”

—Kira Mioducki

Strengths in partnership

While the driving purpose of the partnership is to expand what’s possible for BPS students, GSE stands to gain just as much. The collaboration is already creating valuable experiences for UB students.

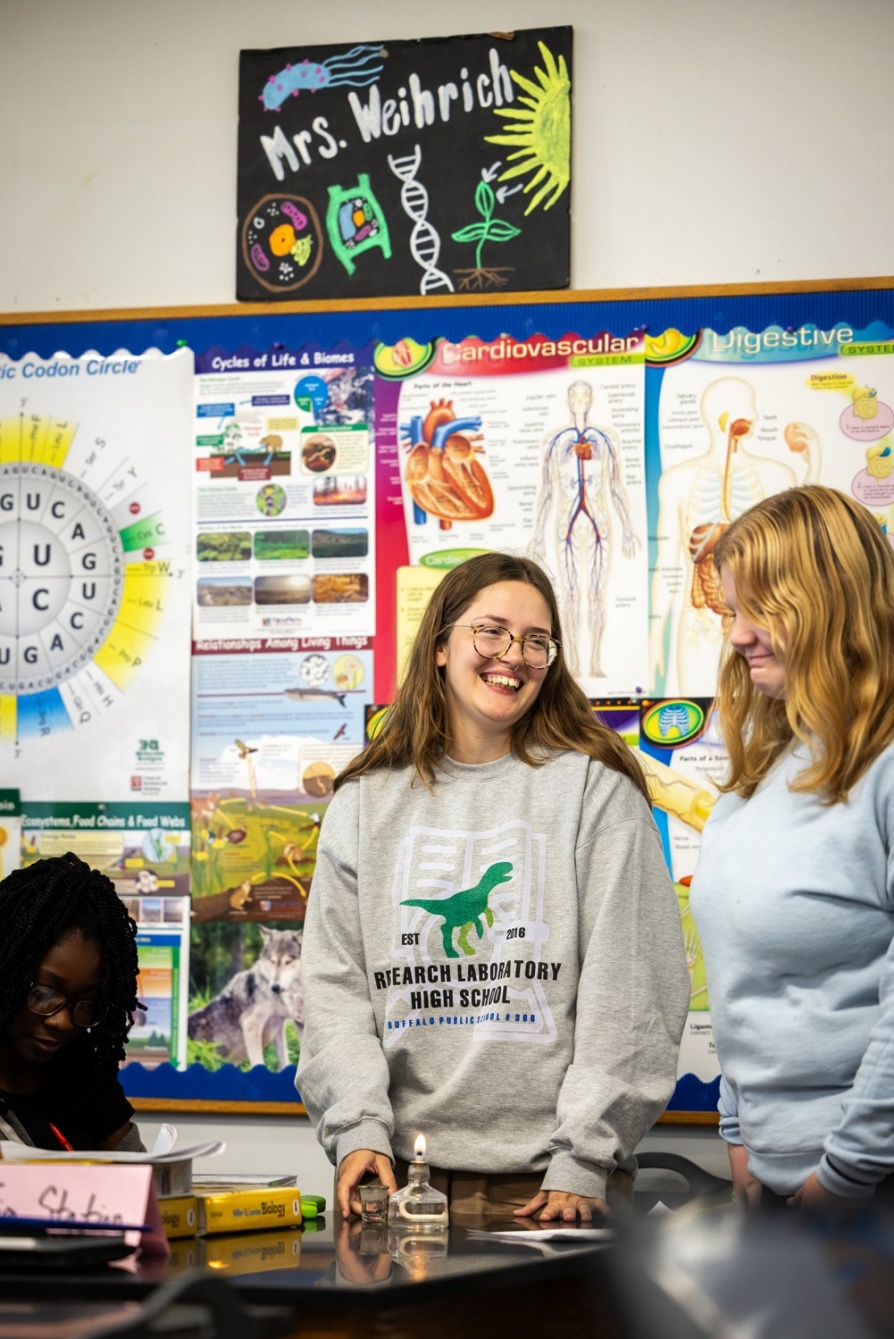

Teacher resident Autumn Ragonese leads a hands-on lesson during her classroom residency experience.

At Research Lab this fall, four GSE teacher residents are embedded alongside the school’s 26 teachers.

“We’re going to work with the teacher residents during the first half of the year, creating what we’re calling a mentor shadowing program,” Cullen explained. “Even though they’re assigned to one teacher, they’ll have the opportunity to shadow all of our teachers and learn different best practices. You might be working with a social studies teacher, but then you’ll spend a week with a math teacher or a physical education teacher. I think that’s really powerful, because you can pick different things that work for different people and see what works for you.”

GSE doctoral student Kate Steilen offers another glimpse of the possibilities. She joined the UACS project after a conversation with Schindel. “She mentioned this project with BPS, and I was really intrigued,” she recalled. “I asked all about it, and then we discussed whether I could be useful. I essentially joined as a grad researcher and observer.”

As both a parent active in BPS and a scholar studying leadership and organizational change, Steilen found the experience uniquely rewarding. “One very striking thing about my participation is watching people who did not have prior relationships decide to work together and find that rhythm, which is complex,” she said. “These systems make decisions differently, so sometimes a meeting is simply about laying the groundwork for what might be. There’s more inquiry than answer in the process.

“As someone new to the field, research can often feel more theoretical. Here, I’m part of a team imagining and enacting a new model of school alongside leaders who are working toward that transformation in real time,” said Steilen.

The partnership also opens up a world of scholarly questions, according to Rosenblith. “Everything about this is researchable,” she said.

Because Research Lab is a non-criterion school—one that admits students without selective requirements—the impact of the model can be measured broadly: Are students better prepared than peers in similar schools? How do computer science and AI integration shape self-efficacy and career aspirations? What happens when expanded counseling support is available?

The questions extend well beyond GSE. As other UB schools introduce academically based community service courses into Research Lab—from architecture to engineering—faculty and students will not only contribute to teaching, but also study how those collaborations reshape learning, mentoring and community engagement. “Every one of those initiatives is its own research project,” Rosenblith emphasized.

In Cipollone’s view, the work underway at Research Lab offers a rare chance to rethink teacher preparation.

“Institutions of teacher preparation do not have a great track record,” she said. “We often either reproduce the problematic systems that exist, or we send graduates into schools with ideas about change that feel impossible to enact, and they burn out. This partnership allows us to connect theory and practice differently, to prepare teachers in ways that are informed by real collaboration with schools.”

From left: Christopher Proctor, Tim Monreal, Kristin Cipollone, Kira Mioducki, Angela Cullen, Kate Steilen, Sandra Small and Karen Murray outside Research Laboratory High School.

As such, the national UACS community is watching Buffalo closely. Schindel notes that UB’s ability to navigate curricular autonomy—a level of freedom other sites have not achieved—sets this work apart. “That’s what people are curious about,” she said. “They want to see what we’ll be able to accomplish, and what gets co-created by students, teachers and professors working side by side. Relationships will be key and sustaining them will take time and resources. But if we get it right, the potential is tremendous.”

Cipollone, who is also the associate director of the UB Teacher Residency Program, agrees. “This isn’t about copying a model and pasting it somewhere else,” she said. “It’s about proving what’s possible when universities and schools come together in real partnership—when teacher autonomy, student voice and community needs are integral to the process. My hope is that we can show there’s a different way of doing this work, one that could inspire change in schools everywhere.”

“Education reflects society, and I think that we need to do a better job of repairing both.”

—Tim Monreal

Repairing education, restoring possibility

At its core, the future of the partnership is about envisioning schools and communities differently.

“Undemocratic forces really try to control and shrink the imaginations of people," said Monreal. "Because if you can’t imagine things to be different, then you’re not going to fight for things to be different … Education reflects society, and I think that we need to do a better job of repairing both.”

Cullen shares that conviction. She envisions the model growing beyond one school, with UB professors co-teaching alongside BPS teachers and other colleges joining in similar collaborations. “You get these wonderful professors from the University at Buffalo who are so passionate about their content, but also really passionate about the city of Buffalo,” she said. “When you put that together with educators who have devoted their lives to this district, really great things can happen. And that’s happening right now.”

For Rosenblith, the vision goes even further. “My question has been: Why can’t these students be the producers of what comes next? Why aren’t the next innovations in technology coming from them?” she asked.

“The real promise is in letting them produce the next breakthroughs, whether in medical research, education, or the arts and humanities. Why can’t these kids be the ones to say, ‘These are the things our communities need and value, and here’s how technology can provide new opportunities?’ That is the promise and the potential of this school and this partnership.”