Research News

Researcher secures grant to study learning in public library ‘makerspace’

UB researchers are studying makerspaces and the people who use them.

By CHARLES ANZALONE

Published November 5, 2018 This content is archived.

All human beings make stuff, UB faculty member Sam Abramovich says. So imagine making something that satisfies a personal, customized need, or solving a problem for your family, or finding a way to express yourself through an art that is as fulfilling as it is fun.

And now look at this through the eyes and thinking of an educational researcher. How does this creative process help people learn? What motivates people to make stuff? How can educators use the desire to make stuff to help people learn?

That’s the essence of a three-year, $346,000 grant secured by Abramovich, assistant professor in the departments of Learning and Instruction, and Library and Information Studies in the Graduate School of Education. He will collaborate with the Buffalo and Erie County Public Library to develop reliable and valid ways to measure the learning and associated benefits of making in libraries.

“There is this concept that we all make things,” says Abramovich, director of UB’s Open Education Research Lab and the grant’s primary investigator. “We all make things every single day. Whether it’s something at work, or something for personal use, or just to fulfill some kind of creative need, or wanting to share with others and wanting to be part of a community. You make things.”

Often these “makers” are limited or hampered because they don’t understand or have access to technology or equipment, he says. Or maybe they just need to talk to like-minded people who share their interests and can offer advice.

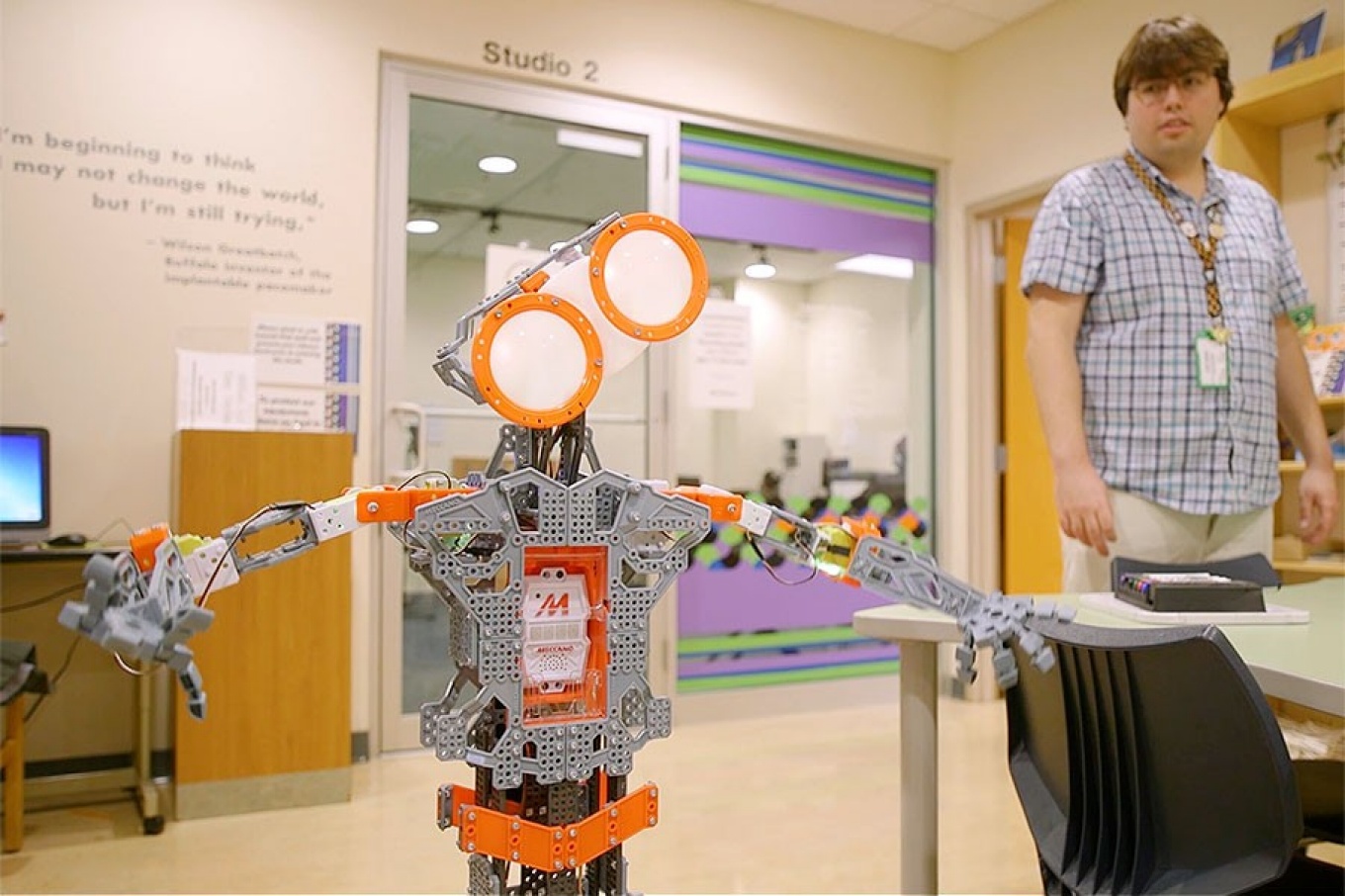

That’s where the emerging and expanding concept of makerspaces and the makerspace culture fits this need. Sometimes they’re called hacker spaces, fab labs, tinker-spaces or DIY (do-it-yourself) spaces. Whatever the name, they’re evidence of a clear, cultural movement for supporting people who are “making stuff,” as Abramovich says. Just like the Launch Pad space at the Buffalo and Erie County Public Library, makerspaces are actual locations where people of all ages can use digital, as well as physical technologies, to create products, explore new ideas and learn technical skills.

So if someone — anyone — has a problem to address, makerspaces are the place to be.

“What you do in the 21st century is go out and design and build things, whether it’s a physical something or whether it’s designing the way people learn, or whether it’s designing software, or designing a program,” says Abramovich, whose other research has been in free “open” educational materials that can be downloaded, edited or shared, as well as the use of digital educational badges to motivate learning.

“And along with making comes all this other good stuff, such as developing STEM and STEAM (science, technology, engineering, arts and mathematics) understanding. Or it’s your ability to engage in design thinking or design-based education.

“Driven by new making technologies, makerspaces are a natural evolution of what libraries can offer their communities,” he says.

The research grant, awarded by the Institute of Museum and Library Services, notes the importance of the Buffalo and Erie County Public Library’s makerspace efforts. And for both Abramovich and the library, evaluation and assessment are crucial.

“Evaluating creative, hands-on learning activities in our public makerspace is critical as libraries continue to evolve and expand services to meet community needs,” says Mary Jean Jakubowski, director of the Buffalo and Erie County Public Library.

“Understanding the value of such services and being able to determine measurable components of learning and education can aid us when seeking and advocating for funding, developing additional partnerships and demonstrating the fundamental realization that libraries are education.”

For Abramovich, evaluation and assessment mean more than just measuring what people learn.

“People hear the word ‘assessment’ and often think of a test or a measure to determine whether someone knows something or not, or how much they know,” he says. “And there is a place and value to that.

“But assessment goes beyond that. Assessment includes helpful feedback. Whether it’s from an instructor to a student, whether it’s from a manager to an employee, whether it’s from a peer to another peer, letting them know what works, what doesn’t work, what you think is good, what is not good, areas for improvement.

“So when we do research into assessment, we want assessment for learning, not just of learning.” Abramovich says. “Our goal is to build a variety of assessments that can help understand learning while making for everyone involved — the library patron, the librarians and the rest of the community.”

Assessment for learning is going to be challenging in the library markerspace because there are so many “moving targets,” he notes. The Launch Pad is an informal learning space, he says, and librarians don’t necessarily know how often people visit, or their prior level of knowledge, or even whether English is their primary language. Many of the factors that educators can rely on in a more structured, traditional setting are not possible in a library.

“Nonetheless, we can observe,” Abramovich says. “We can see there is good, valuable, important learning going on in this space. So how do we build the tools to help these library patrons using these spaces? How do we help the librarians, and how do we help the outside stakeholders, like the politicians and board of library governors? How do we help them get the data, the information to support and improve the learning going on in this makerspace?

“How do we build assessments that tell us how people are learning, what people are learning and what is their motivation for learning?”

The Launch Pad at the downtown library is a bright, inviting space in a hard-to-miss location. From organizing origami and finger-painting workshops to two fully equipped production studios where people can develop their own videos and music, the Launch Pad makerspace is a diverse resource for the do-it-yourself state of mind, using both high- and lower-tech approaches.

Library patrons have access to equipment and space at the Buffalo and Erie County Public Library's Launch Pad.

Available equipment and projects include:

A 3D printer: Similar to how people print pictures and text on a regular printer, library patrons can create a blueprint of a three-dimensional object that the 3D printer will then build out of plastic filament. Patrons use it create whatever they can design, from obscure repair parts to complex artistic sculptures.

Studio Space: Two production studios with advanced video and audio equipment are available to library patrons. They allow anyone to create professional-grade video and audio for whatever purpose they want.

Virtual reality equipment: Visitors to the library can come to the Launch Pad to experiment with state-of-the-art virtual reality equipment. All ages can see what modern VR experiences are like, as well as experiment with VR equipment that is intended for wider uses.

Abramovich also will work with the University of Wisconsin and the Madison Public Library on the grant. The data collected will be valuable for the increasing number of libraries across the country that have started makerspaces. Abramovich plans to develop a suite of openly licensed educational tools and regional workshops to help local makerspaces better use measures of learning.

“Makerspaces aren’t just for libraries of the future; they are here now and they are meeting an important need,” he says, “and we need to use research to better support them.”